You no doubt have heard much discussion of the effects of El Nin᷉o and La Nin᷉a on our weather patterns and how these phenomena are used to predict weather—like the number of hurricanes in a season, how cold the winter will be or how hot the summer will be.

Let’s start with defining these two weather patterns.

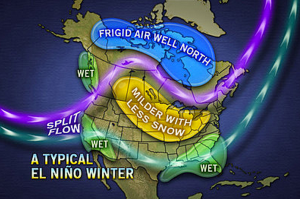

El Nin᷉o is a warm ocean current that often develops in late December every 4 to 12 years in the eastern and central Pacific Ocean near the equator. El Nin᷉o—Spanish for “the little boy” and sometimes associated with the Christ child because of it’s late December appearance—can cause unusual global weather conditions.

El Nin᷉o is a warm ocean current that often develops in late December every 4 to 12 years in the eastern and central Pacific Ocean near the equator. El Nin᷉o—Spanish for “the little boy” and sometimes associated with the Christ child because of it’s late December appearance—can cause unusual global weather conditions.

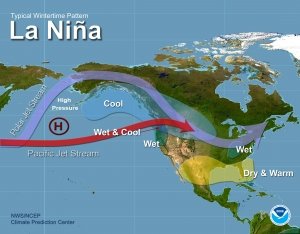

It’s opposite is La Nin᷉a which is Spanish for “the little girl.” La Nin᷉a is an extensive cooling of the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean which is often accompanied by warmer than normal sea surface temperatures in the western Pacific and to the north of Australia. In the US La Nin᷉a can cause above-average precipitation across the northern Midwest, the northern Rockies, Northern California, and the Pacific Northwest. In the southwestern and southeastern states precipitation tends to be below average.

This year we are experiencing an El Nin᷉o which is predicted to become one of the strongest on record and be a big influence on weather patterns this winter.

This year we are experiencing an El Nin᷉o which is predicted to become one of the strongest on record and be a big influence on weather patterns this winter.

The Union of Concerned Scientists has monitored the development of this year’s El Nin᷉o and reports that the “autumn conditions (October to November) rank as the third largest El Nin᷉o since 1950.”

El Nin᷉o tends to create a subtropical, low-latitude jet stream that brings a lot of moisture and cooler temperatures to the southern US, including California, warmer weather to western Canada and southern Alaska, drier weather to the Pacific Northwest, and cooler weather to northern Canada.

All indications are that this year’s massive El Nin᷉o pattern could keep Arctic air out of much of the US well into the winter. Jan Null of Golden Gate Weather Services reported that November water temperatures in the Pacific were the warmest on record.

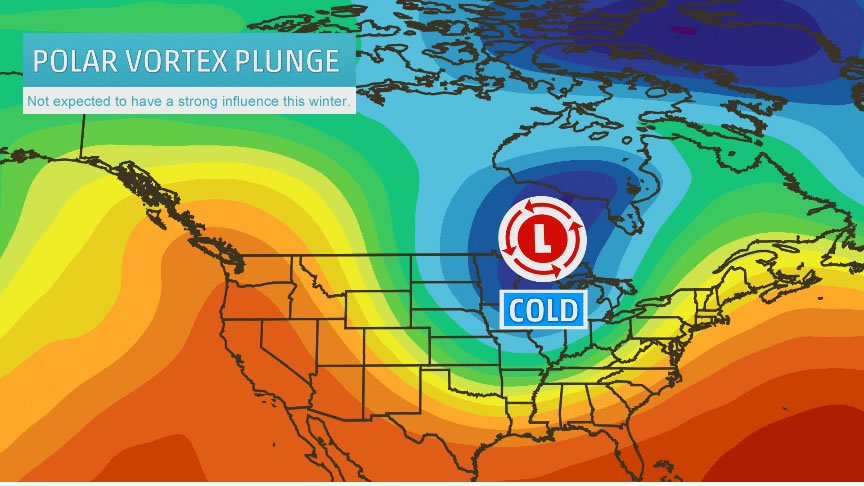

Another major weather influence comes from the Arctic—specifically how the temperatures north of 60 degrees latitude influence the polar vortex in the winter.

A polar vortex is a persistent large-scale cyclone, circling the planet’s geographical poles and extending 5 miles to 30 miles above the earth’s surface up into the stratosphere. It exists throughout the year but is strongest during winter when the air within the polar vortex is the coldest. This strong atmospheric circulation forms a “wall” or “fence” that confines the cold Arctic air within the circulation to the polar region. In the Northern Hemisphere circumstances can occur that weaken the polar vortex even in the winter. This happened in the 2013-2014 winter, and the cold Arctic air spilled down into North American territories that don’t usually see such extremely cold temperatures.

During the 2013-2014 winter the energy demand was so great that natural gas prices were sustained for the bulk of 2014 and into 2015 due to the lower storage inventories it caused. When there’s a strong polar vortex and the Arctic cold is contained in the polar regions, the lack of winter weather in the US and the lack of demand can cause price depression.

In recent weeks meteorologists have noticed that there is a strong polar vortex so far this year, so the Arctic cold has been contained in the Polar Regions and is not seeping down into the lower 48. They predict we will experience a mild, warmer than average northern half of the country and a colder than normal southern half for the remaining winter months. But there are others who say the polar vortex may weaken in January. If it weakens it becomes wobbly and sets up southward blasts of frigid air.

The northern half includes the densely populated, heavy natural gas consuming regions of the Midwest and Northeast.

Currently El Nin᷉o is providing westerly winds across Canada that are keeping the polar vortex strong and locked up near the Arctic Circle.

With this information, we can make a few predictions about what could happen if a prolonged warm streak continues through the remaining four months of winter.

Here’s what we have:

• Warmer-than-normal temperatures in November

• Record inventory levels of natural gas

• Production growth

• And forecasts for a warmer winter

All of this contributes to natural gas prices remaining at low levels.

Weather is extremely important when it comes to energy demand. And warmer weather creates a lower demand.

The market is ultimately dependent on the weather and so we are experiencing lower prices.